- Home

- Jorge Carrión

Bookshops

Bookshops Read online

Biblioasis International Translation Series

General Editor: Stephen Henighan

1. I Wrote Stone: The Selected Poetry of

Ryszard Kapuściński (Poland)

Translated by Diana Kuprel and Marek Kusiba

2. Good Morning Comrades

by Ondjaki (Angola)

Translated by Stephen Henighan

3. Kahn & Engelmann

by Hans Eichner (Austria-Canada)

Translated by Jean M. Snook

4. Dance with Snakes

by Horacio Castellanos Moya (El Salvador)

Translated by Lee Paula Springer

5. Black Alley

by Mauricio Segura (Quebec)

Translated by Dawn M. Cornelio

6. The Accident

by Mihail Sebastian (Romania)

Translated by Stephen Henighan

7. Love Poems

by Jaime Sabines (Mexico)

Translated by Colin Carberry

8. The End of the Story

by Liliana Heker (Argentina)

Translated by Andrea G. Labinger

9. The Tuner of Silences

by Mia Couto (Mozambique)

Translated by David Brookshaw

10. For as Far as the Eye Can See

by Robert Melançon (Quebec)

Translated by Judith Cowan

11. Eucalyptus

by Mauricio Segura (Quebec)

Translated by Donald Winkler

12. Granma Nineteen and the Soviet’s Secret

by Ondjaki (Angola)

Translated by Stephen Henighan

13. Montreal Before Spring

by Robert Melançon (Quebec)

Translated by Donald McGrath

14. Pensativities: Essays and Provocations

by Mia Couto (Mozambique)

Translated by David Brookshaw

15. Arvida

by Samuel Archibald (Quebec)

Translated by Donald Winkler

16. The Orange Grove

by Larry Tremblay (Quebec)

Translated by Sheila Fischman

17. The Party Wall

by Catherine Leroux (Quebec)

Translated by Lazer Lederhendler

18. Black Bread

by Emili Teixidor (Catalonia)

Translated by Peter Bush

19. Boundary

by Andrée A. Michaud (Quebec)

Translated by Donald Winkler

20. Red, Yellow, Green

by Alejandro Saravia (Bolivia-Canada)

Translated by María José Giménez

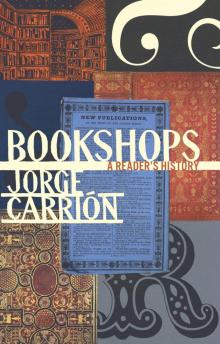

21. Bookshops: A Reader’s History

by Jorge Carrión (Spain)

Translated by Peter Bush

BOOKSHOPS

A Reader’s History

Jorge Carrión

BOOKSHOPS

A Reader’s History

Translated from the Spanish by

Peter Bush

BIBLIOASIS

WINDSOR, ON

Copyright © Jorge Carrión, 2017

First published in the Spanish language as Librerías by Editions Anagrama, Barcelona in 2013

Translation copyright © Peter Bush, 2017

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher or a licence from The Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (Access Copyright). For an Access Copyright licence, visit www.accesscopyright.ca or call toll free to 1-800-893-5777.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Carrión, Jorge, 1976-

[Librerías. English]

Bookshops : a reader’s history / Jorge Carrión.

(Biblioasis international translation series ; no. 21)

Translation of: Librerías.

Translated from the Spanish by Peter Bush.

Issued in print and electronic formats.

ISBN 978-1-77196-174-5 (hardcover).--ISBN 978-1-77196-175-2 (ebook)

1. Bookstores. 2. Books and reading. 3. Authors--Books and reading.

I. Title. II. Title: Librerías. English. III. Series: Biblioasis international translation series ; no. 21

Z278.C3113 2017 070.5 C2017-901938-4

C2017-901939-2

Readied for the Press by Daniel Wells

Copy-edited by Emily Donaldson

Typeset by Chris Andrechek

Jacket Designed by Jeffrey Fisher

A bookshop is only an idea in time.

Carlos Pascual, “The Power of a Reader”

I do not doubt that I often happen to talk of things which are treated better in the writings of master-craftsmen, and with more authenticity. What you have here is purely an assay of my natural, not at all of my acquired, abilities. Anyone who catches me out in ignorance does me no harm: I cannot vouch to other people for my reasonings: I can scarcely vouch for them to myself and am by no means satisfied with them. If anyone is looking for knowledge let him go where such fish are to be caught: there is nothing I lay claim to less. These are my own thoughts, by which I am striving to make known not matter but me.

Michel de Montaigne, “On Books,”

translated by M. A. Screech

A man recognizes his genius only upon putting it to the test. The eaglet trembles like the young dove at the moment it first unfolds its wings and entrusts itself to a breath of air. When an author composes a first work, he does not know what it is worth, nor does the bookseller. If the bookseller pays us as he wishes, we in turn sell him what we are pleased to sell him. It is success that instructs the merchant and the man of letters.

Denis Diderot, “Letter on the Book Trade”

translated by Arthur Goldhammer

Introduction

Inspired by a Stefan Zweig Short Story

The way a specific story relates to the whole of literature is similar to the way a single bookshop relates to every bookshop that exists, has existed and will ever perhaps exist. Synecdoche and analogy are the two most useful figures of speech: I shall start by talking about all bookshops from the past, present and whatever the future may hold via one story, “Mendel the Bibliophile,” written in 1929 by Stefan Zweig and set in Vienna in the twilight years of empire, and will then move on to other stories that speak of readers and books in the course of a frenzied twentieth century.

Zweig does not choose a renowned Viennese café for his setting, not the Frauenhuber or the Imperial, one of the cafés that were the best academies for studying the latest fashions—as he says in The World of Yesterday—but an unknown café; the story starts when the narrator goes to “the outer districts of the city.” He is caught in the rain and takes shelter in the first place he finds. Once seated at a table, he is struck by a feeling of familiarity. He glances at the furniture, the tables, billiard tables, chessboard and telephone box, and senses that he has been there before. He scours his memory until he remembers with a sharp jolt.

He is in the Café Gluck, where the bookseller Jakob Mendel had once sat, each and every day from 7.30 a.m. to closing time, surrounded by heaps of his catalogues and books. Mendel would peer through his spectacles memorizing his lists and data, and sway his chin and curly ringlets in a prayer-like rhythm: he had come to Vienna intending to study for the rabbinate, but antique books had seduced him from that path, “so he could give himself up to idolatry

in the form of the brilliant, thousand-fold polytheism of books,” and thereby become the Great Mendel. Because Mendel had “a unique marvel of a memory,” he was considered “a bibliographical phenomenon,” “a miraculum mundi, a magical catalogue of all the books in the world,” “a Titan”:

Behind that chalky, grubby brow, which looked as if it were overgrown by grey moss, there stood in an invisible company, as if stamped in steel, every name and title that had ever been printed on the title page of a book. Whether a work had first been published yesterday or two hundred years ago, he knew at once its exact place of publication, its publisher and the price, both new and second-hand, and at the same time he unfailingly recollected the binding, illustrations and facsimile editions of every book [. . .] he knew every plant, every micro-organism, every star in the eternally oscillating, constantly changing cosmos of the universe of books. He knew more in every field than the experts in that field, he was more knowledgeable about libraries than the librarians themselves, he knew the stocks of most firms by heart better than their owners, for all their lists and card indexes, although he had nothing at his command but the magic of memory, nothing but his incomparable faculty of recollection, which could only be truly explained and analysed by citing a hundred separate examples.

The metaphors are beautiful: his brow looks “overgrown by grey moss,” the books he has memorized are species or stars and constitute a community of phantoms, a textual universe. His knowledge as an itinerant seller without a licence to open a bookshop is greater than that of any expert or librarian. His portable bookshop, with its ideal location on a table—always the same one—in the Café Gluck, is now a shrine of pilgrimage for all lovers and collectors of books, as well as all the people who could not find the bibliographical references they had been looking for via more official routes. After an unhappy experience in a library, the narrator, a young university student, is taken to the legendary café table by a friend, a guide, who reveals to him a secret place that does not appear in guidebooks or on maps, one that is only known to the initiated.

One could include “Mendel the Bibliophile” in a series of contemporary stories that focus on the relationship between memory and reading, a series that might start in 1909 with “A World of Paper” by Luigi Pirandello and finish in 1981 with The Encyclopedia of the Dead by Danilo Kiš, by way of Zweig’s story and the three Jorge Luis Borges wrote in the middle of the last century. The old meta-book tradition reaches such a level of maturity and transcendence in the world of Borges that we are duty-bound to consider what comes before and after each of his stories as precursors and heirs. “The Library of Babel,” from 1941, describes a hyper-textual universe in the form of a library hive devoid of meaning, one in which reading is almost exclusively a matter of deciphering (an apparent paradox: in Borges’ story reading for pleasure is banned). Published in Sur four years later, “The Aleph” is about how one might read “The Library of Babel” if it were reduced to the tiniest sphere that condenses the whole of space and time. And above all, it is about the possible translation of such a reading into a poem, into language that makes of the portentous Aleph’s existence something useful. But “Funes the Memorious,” from 1942, is undoubtedly the Borges story that most reminds us of Zweig’s, with its protagonist who lives on the edge of Western civilisation, and who, like Mendel, is an incarnation of the genius of memory:

Babylon, London and New York have overawed the imagination of men with their ferocious splendour; no-one in those populous towers, or upon those surging avenues, has felt the heat and the pressure of a reality as indefatigable as that which day and night converged upon the unfortunate Irineo in his humble South American farmhouse.

Like Mendel, Funes does not enjoy his amazing gifts of recall. Reading does not involve a process of unravelling plots for either of them, nor is it about investigating life patterns, understanding psychological states, abstracting, relating, thinking, experiencing fear and pleasure on their nerve-endings. Just as it is for Number 5, the robot in the film Short Circuit, which appeared forty-four years later, reading for them is about absorbing data, myriad labels, indexing and processing information: desire is excluded. The stories by Zweig and Borges complement each other entirely: old man and young, the total recall of books and the exhaustive recall of the world, the Library of Babel in a single brain and the Aleph in a single memory, both characters united by their poverty-stricken, peripheral status.

In “A World of Paper,” Pirandello also imagines a reading scenario beset by poverty and obsession. A compulsive reader to the extent that his skin replicates the colour and texture of the paper, but deep in debt because of his habit, Balicci is going blind: “His whole world used to be there! And now he could not live there, except for that small area his memory brought back to him!” Reduced to a tactile reality, to volumes as disorganized as pieces of the Tetris, he decides to contract someone to classify his books, to bring order to his library, so that his world is “rescued from chaos.” However, he subsequently feels incomplete and orphaned because he finds it impossible to read. He hires a woman reader, Tilde Pagliocchini, whose voice and intonation annoy him so much that the only solution they can find is for her to read extremely quietly—that is, silently—so that he can imagine his own, ever-diminishing reading habit from the speed at which she covers lines and pages. His whole world, re-ordered in memory.

A world that can be encompassed and shrunk thanks to the metaphor of the library, a portable library or photographic memory that can be described and mapped.

It is not merely fortuitous that the protagonist of The Encyclopedia of the Dead by Danilo Kiš is, in fact, a topographer. His whole life has been determined in minute detail by a kind of sect or band of anonymous scholars who, from the end of the eighteenth century, have been pursuing an encyclopedic project—parallel to that of the Enlightenment—which includes everyone in history not to be found in all the other official or public encyclopedias available for consultation in any library. The story goes on to speculate about the existence of a Nordic library where one might find the rooms—each allocated a letter of the alphabet—of The Encyclopedia of the Dead, one where every volume is chained to its shelf and is impossible to copy or reproduce, the object of partial readings that are immediately forgotten.

“My memory, sir, is like a garbage disposal,” says Funes. Borges always speaks of failure: the three wonders he has conjured up amount to gestures in the face of death and the absurd. We know how foolish these lines are that Carlos Argentino was able to write with the inspiration of the incredible Aleph, the possession of which he irrevocably squandered. And Borges’ librarian, a persistent explorer of the library’s nooks and crannies, lists in his old age all the certainties and expectations humanity has gradually discarded over the centuries, affirming at the end of his report, “I know of districts where the youth prostrate themselves before books and barbarously kiss the pages, though they do not know how to make out a single letter.” We find the same elegiac tone in the stories I have mentioned: Pirandello’s hero goes blind, Mendel is killed, the Library of Babel loses habitués to lung disease and suicide, Beatriz Viterbo has died, the father of Borges is ill and Funes dies of congestion. The father of Kiš’s narrator also disappears. What links the six stories is an individual and a world in mourning: “Memory of indescribable melancholy: walking many a night along gleaming passageways and stairs and not finding a single librarian.”

So I was overcome by a kind of horror when I saw that the marble-topped table where Jakob Mendel made his oracular utterances now stood in the room as empty as a gravestone. Only now that I was older did I understand how much dies with such a man, first because anything unique is more and more valuable in a world now becoming hopelessly uniform.

Mendel’s extraordinary nature, says Zweig, could only be recounted through examples. To describe the Aleph, Borges has recourse to the chaotic enumeration of separate fragments of a body that is capable of proc

essing the universal. Post-Borges, Kiš emphasizes how each of the cases he mentions is but a small part of the material indexed by his anonymous sages. A table in a local café can be the tiny key to the doors of the superimposed layers of a vast city. And one man can have the key that gives access to a world that ignores geo-political frontiers, that understands Europe as a unique cultural space beyond wars or the fall of empires. A cultural space that is always hospitable, because it only exists within the minds of those who walk and travel there. Unlike Borges, for whom history is unimportant, Zweig is keen to talk about how the First World War invented present-day frontiers. Mendel had lived his whole life in peace, without a single document to prove his original nationality or authorize his residency in the country where he was living. The news that war has broken out never reaches his bookish world and the postcards he continues to send to booksellers in Paris or London—those enemy capitals—suddenly attract the attention of the censor (a reader who is central to the history of the persecution of books, a reader who spends his time betraying readers). The secret police discover that Mendel is Russian and therefore a potential enemy. He loses his glasses in a skirmish. He is interned in a concentration camp for two years, during which time reading, his most beloved, pressing, perpetual activity, is interrupted. He is released thanks to important, influential clients, book collectors who know the man is a genius. But when he returns to the café, he finds he has lost the ability to read as he once did and thus spirals irreversibly towards eviction and death.

It is significant that he is a wandering Jew, a member of the People of the Book, that he comes from the East and meets misfortune and his end in the West, even though this only happens after dozens of years of unconscious assimilation, of being respected and even venerated by the chosen few who recognize that he is indeed exceptional. Mendel’s relationship with printed information, Zweig tells us, caters to all his erotic needs. Like the ancient sages of Africa, he is a library man and his world is the non-material, accumulated energy that he shared.

Bookshops

Bookshops